Nos últimos dias estive ocupado em finalizar a quarta edição do livro Teoria da Contabilidade, em co-autoria com o professor Jorge Katsumi. Muitas alterações. E usei muito o blog para inspirar em algumas partes que fiquei responsável. Vários exercícios tem sua fonte no blog. Eis um trecho da apresentação, onde estão detalhadas as alterações na nova edição:

Esta quarta edição traz alterações profundas. Já incorporamos aqui os aspectos que sofreram alteração com a nova estrutura conceitual do Iasb, aprovada no início de 2018. Também alteramos todos exercícios no final de cada capítulo, que representa uma atualização das discussões. A seção sobre pesquisa, que existia no final de cada capítulo, foi suprimida. O volume de pesquisas existentes em cada tópico é cada vez maior, tornando difícil para os autores manter este ponto de forma adequada e justa. Optamos por inserir no final de cada capítulo, quando couber, um tema emergente.

No capítulo 1, deixamos claro a diferença entre regulação e padronização, optando por usar o primeiro termo. Discutimos também o texto como informação, já que esta é uma área que está sendo objeto de análise e atenção da teoria. E incluímos o princípio da evidenciação plena. No capítulo 2, fizemos uma atualização das mudanças recentes na estrutura do Iasb. Em razão dos rumos da convergência internacional das normas contábeis, o capítulo 3 foi alterado e atualizado. O resultado é um capítulo mais enxuto em relação às edições anteriores.

O capítulo 5 é novo e trabalha a questão da estrutura conceitual. O capítulo inicia descrevendo as premissas básicas da contabilidade. O capítulo discute as vantagens e desvantagens de se ter uma estrutura conceitual, assim como as razões que levam as mudanças nesta estrutura. Um aspecto específico da estrutura, a questão da prudência, é objeto de discussão. O capítulo encerra contemplando o papel do CPC na contabilidade brasileira.

O Capítulo 6 reúne material novo sobre a teoria da mensuração, além de apresentar, de maneira mais resumida, a questão da inflação. Assim, a discussão sobre mensuração, que constava do capítulo do Ativo passa a compor este capítulo.

O capítulo sobre o Ativo, o de número 7, foi atualizado com as novas definições da estrutura conceitual de 2018. Isto inclui uma discussão sobre desreconhecimento. Os temas “intangível” e “recuperabilidade” foram agregados a este capítulo. A discussão sobre a relevância da incerteza e da probabilidade foi expandida nesta nova edição. Também discutimos o problema da primazia conceitual dos termos ativo e passivo. Ao final do capítulo iniciamos uma discussão sobre ativos virtuais.

O capítulo 8 é resultado da junção dos antigos capítulos de passivo e patrimônio líquido. A experiência didática revelou que não existia uma necessidade de um capítulo específico para o patrimônio líquido e por este motivo os autores optaram por esta medida. Pequenas atualizações foram feitas no capítulos

No capítulo 9 incorporamos a discussão sobre o reconhecimento da receita de incorporadoras e inserimos um texto sobre a qualidade do lucro.

O capítulo do setor público foi reformulado, com a inclusão de uma abordagem histórica e os avanços recentes na área, incluindo a convergência das normas internacionais no Brasil e a abordagem conceitual do IFAC, baseada na abordagem do Iasb. Também melhoramos a abordagem histórica do capítulo.

Na parte do terceiro setor, fizemos pequenas atualizações. Finalmente, o capítulo de leasing foi reformulado diante das novas normas. Este capítulo contou com a participação da pesquisadora Nyalle Barboza Matos.

Obviamente que a capa também será alterada.

21 junho 2019

Práticas Administrativas importam?

Um artigo, publicado na American Economic Review, busca responder uma velha questão: afinal, a prática administrativa faz diferença? Os autores usaram dados de 35 mil fábricas (é isto mesmo, não errei o número) ou 70 mil observações, de uma pesquisa obrigatória feita pelo governo dos Estados Unidos entre 2010 e 2015. O foco é verificar se existe uma relação entre administração e desempenho. Com base em um questionário desenhado pelo Banco Mundial, aplicou uma pesquisa denominada de Managemente and Organizational Practices Survey. Entre as perguntas, questões sobre monitoramente, metas e incentivos. Foco da análise ficou nos direcionadores de práticas administrativas relacionadas com o ambiente de negócios e o spillover (transbordamento). Com um índice de resposta de 75% a pesquisa mostrou que

a) Há uma grande variação nas práticas administrativas. A surpresa é que isto é válido também para fábricas de uma mesma empresa. Além disto, quanto maior a empresa, maior esta variação.

b) Usando dados de duas regiões que estavam concorrendo entre si para receber uma indústria, os autores mostraram que spillovers positivos ocorreram quando também existia fluxos frequentes na mão-de-obra gerencial. Em outras palavras, será no movimento dos gerentes (não dos executivos ou dos trabalhadores ou da governança corporativa) que ocorrerá um mecanismo de aprendizado

Bloom, N., Brynjolfsson, E., Foster, L., Jarmin, R., Patnaik, M., Saporta-Eksten, I., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). What drives differences in management practices?. American Economic Review, 109(5), 1648-83.

a) Há uma grande variação nas práticas administrativas. A surpresa é que isto é válido também para fábricas de uma mesma empresa. Além disto, quanto maior a empresa, maior esta variação.

b) Usando dados de duas regiões que estavam concorrendo entre si para receber uma indústria, os autores mostraram que spillovers positivos ocorreram quando também existia fluxos frequentes na mão-de-obra gerencial. Em outras palavras, será no movimento dos gerentes (não dos executivos ou dos trabalhadores ou da governança corporativa) que ocorrerá um mecanismo de aprendizado

Bloom, N., Brynjolfsson, E., Foster, L., Jarmin, R., Patnaik, M., Saporta-Eksten, I., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). What drives differences in management practices?. American Economic Review, 109(5), 1648-83.

Hackeando Blockchain

Once hailed as unhackable, blockchains are now getting hacked

More and more security holes are appearing in cryptocurrency and smart contract platforms, and some are fundamental to the way they were built.

Early last month, the security team at Coinbase noticed something strange going on in Ethereum Classic, one of the cryptocurrencies people can buy and sell using Coinbase’s popular exchange platform. Its blockchain, the history of all its transactions, was under attack.

An attacker had somehow gained control of more than half of the network’s computing power and was using it to rewrite the transaction history. That made it possible to spend the same cryptocurrency more than once—known as “double spends.” The attacker was spotted pulling this off to the tune of $1.1 million. Coinbase claims that no currency was actually stolen from any of its accounts. But a second popular exchange, Gate.io, has admitted it wasn’t so lucky, losing around $200,000 to the attacker (who, strangely, returned half of it days later).

Just a year ago, this nightmare scenario was mostly theoretical. But the so-called 51% attack against Ethereum Classic was just the latest in a series of recent attacks on blockchains that have heightened the stakes for the nascent industry.

In total, hackers have stolen nearly $2 billion worth of cryptocurrency since the beginning of 2017, mostly from exchanges, and that’s just what has been revealed publicly. These are not just opportunistic lone attackers, either. Sophisticated cybercrime organizations are now doing it too: analytics firm Chainalysis recently said that just two groups, both of which are apparently still active, may have stolen a combined $1 billion from exchanges.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.

That’s been understood, at least in theory, since Bitcoin emerged a decade ago. But in the past year, amidst a Cambrian explosion of new cryptocurrency projects, we’ve started to see what this means in practice—and what these inherent weaknesses could mean for the future of blockchains and digital assets.

More and more security holes are appearing in cryptocurrency and smart contract platforms, and some are fundamental to the way they were built.

Early last month, the security team at Coinbase noticed something strange going on in Ethereum Classic, one of the cryptocurrencies people can buy and sell using Coinbase’s popular exchange platform. Its blockchain, the history of all its transactions, was under attack.

An attacker had somehow gained control of more than half of the network’s computing power and was using it to rewrite the transaction history. That made it possible to spend the same cryptocurrency more than once—known as “double spends.” The attacker was spotted pulling this off to the tune of $1.1 million. Coinbase claims that no currency was actually stolen from any of its accounts. But a second popular exchange, Gate.io, has admitted it wasn’t so lucky, losing around $200,000 to the attacker (who, strangely, returned half of it days later).

Just a year ago, this nightmare scenario was mostly theoretical. But the so-called 51% attack against Ethereum Classic was just the latest in a series of recent attacks on blockchains that have heightened the stakes for the nascent industry.

In total, hackers have stolen nearly $2 billion worth of cryptocurrency since the beginning of 2017, mostly from exchanges, and that’s just what has been revealed publicly. These are not just opportunistic lone attackers, either. Sophisticated cybercrime organizations are now doing it too: analytics firm Chainalysis recently said that just two groups, both of which are apparently still active, may have stolen a combined $1 billion from exchanges.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.

That’s been understood, at least in theory, since Bitcoin emerged a decade ago. But in the past year, amidst a Cambrian explosion of new cryptocurrency projects, we’ve started to see what this means in practice—and what these inherent weaknesses could mean for the future of blockchains and digital assets.

[...]

Fonte: aqui

20 junho 2019

Discussão sem fim: conceito de passivo

Pelo visto, a nova estrutura conceitual Iasb-Fasb não foi suficiente. O FASB, que possui o melhor padrão do mundo, continua discutindo o conceito de passivo. Desde 2017 e ainda não acabou. Segundo uma reunião de fevereiro de 2019 (divulgado agora):

The Board continued its discussion of the definition of a liability. The Board decided that:

All present obligations to transfer assets and obligations to deliver shares sufficient in number to satisfy a determinable or defined obligation should meet the definition of a liability.

An analysis discussing the measurement of obligations to issue a fixed number of shares is unnecessary for the Board to deliberate on in the elements phase.

Além disto, o Fasb decidiu por uma divisão da terminologia das medidas de mensuração diferente do Iasb.

There are three categories of initial measurement:

Entry price

Exit price

Estimated future cash flows.

Exit price is appropriate as an initial carrying amount of an asset when the subsequent measure of the asset will be at exit price.

For transactions in which something other than cash is exchanged, the initial measure of an asset may be based on the exit price for the asset transferred.

The overall objective in identifying costs to be included in the initial carrying amount of an asset at entry price should be to capture the costs incurred to bring the asset to the location and condition necessary for it to be capable of operation.

The following categories help identify the types of costs that should be included in an initial carrying amount consistent with the objective described in (4):

Government-imposed charges

Costs of services related to the acquisition of the asset and readying the asset for use

Costs to participate in the market for the asset.

Gains and losses on cash flow hedges are neither part of the entry price of assets nor a cost to be included in initial carrying amounts of assets based on the objective and categories described in (4) and (5), respectively.

The Board directed the staff to develop a revised project plan to address the elements of financial statements (which are currently defined in FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, Elements of Financial Statements) concurrently with presentation and measurement concepts.

The Board continued its discussion of the definition of a liability. The Board decided that:

All present obligations to transfer assets and obligations to deliver shares sufficient in number to satisfy a determinable or defined obligation should meet the definition of a liability.

An analysis discussing the measurement of obligations to issue a fixed number of shares is unnecessary for the Board to deliberate on in the elements phase.

Além disto, o Fasb decidiu por uma divisão da terminologia das medidas de mensuração diferente do Iasb.

There are three categories of initial measurement:

Entry price

Exit price

Estimated future cash flows.

Exit price is appropriate as an initial carrying amount of an asset when the subsequent measure of the asset will be at exit price.

For transactions in which something other than cash is exchanged, the initial measure of an asset may be based on the exit price for the asset transferred.

The overall objective in identifying costs to be included in the initial carrying amount of an asset at entry price should be to capture the costs incurred to bring the asset to the location and condition necessary for it to be capable of operation.

The following categories help identify the types of costs that should be included in an initial carrying amount consistent with the objective described in (4):

Government-imposed charges

Costs of services related to the acquisition of the asset and readying the asset for use

Costs to participate in the market for the asset.

Gains and losses on cash flow hedges are neither part of the entry price of assets nor a cost to be included in initial carrying amounts of assets based on the objective and categories described in (4) and (5), respectively.

The Board directed the staff to develop a revised project plan to address the elements of financial statements (which are currently defined in FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, Elements of Financial Statements) concurrently with presentation and measurement concepts.

Criptomoedas são inúteis

De acordo com o Professor de Criptografia de Harvard Bruce Schneier, as criptomoedas são inúteis:

Cryptocurrency is useless to anyone other than nefarious groups or individuals trying to move money without being noticed by the government. This is apparently the cutting-edge opinion of Harvard University cryptographer and technology researcher Bruce Schneier.

Citing a series of regularly discredited and debunked talking points, Schneier believes that the aims of Bitcoin according to its original whitepaper have been defeated by the reality of its deployment, which means that in addition to being operationally difficult and risky, it also fails to deliver on its basic premise, which essentially renders it useless

While the other criticisms may have had some measure of technical accuracy, Schneier also cites the hackneyed “crypto-mining-uses-vast-amount-of-energy” argument to back up his belief that cryptocurrency is pointless. According to him – you’ve certainly never heard this before – it constitutes a large environmental hazard due to the amount of energy it consumes.

Schneier argues that bitcoin transaction charges such as processing fees are hidden, unlike bank charges which can be easily calculated. Where he gets the impression that crypto transaction fees are hidden is anyone’s guess at this point, but it certainly makes a good – if inaccurate – talking point.

He also says that automated systems cannot be fully trusted and human input will always be better, adding that blockchain technology is only theoretically trustless. Practically, he says, crypto users still have to trust cryptocurrency exchanges and wallets when they trade or otherwise make transactions. Unsurprisingly, no mention is made of decentralised exchanges, which apparently are not good talking points for the purpose of Schneier’s polemic.

Rounding up his attack on cryptocurrencies, Schneier states that blockchain immutability is a problem because in the event of a mistake, “all of your life savings could be gone.” In his view, cryptocurrency is inherently useless and not needed.

Citing a series of regularly discredited and debunked talking points, Schneier believes that the aims of Bitcoin according to its original whitepaper have been defeated by the reality of its deployment, which means that in addition to being operationally difficult and risky, it also fails to deliver on its basic premise, which essentially renders it useless

Expanding further on this point he says:

“If your bitcoin exchange gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If your bitcoin wallet gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If you forget your login credentials, you lose all of your money. If there’s a bug in the code of your smart contract, you lose all of your money. If someone successfully hacks the blockchain security, you lose all of your money. In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit?

Schneier argues that bitcoin transaction charges such as processing fees are hidden, unlike bank charges which can be easily calculated. Where he gets the impression that crypto transaction fees are hidden is anyone’s guess at this point, but it certainly makes a good – if inaccurate – talking point.

He also says that automated systems cannot be fully trusted and human input will always be better, adding that blockchain technology is only theoretically trustless. Practically, he says, crypto users still have to trust cryptocurrency exchanges and wallets when they trade or otherwise make transactions. Unsurprisingly, no mention is made of decentralised exchanges, which apparently are not good talking points for the purpose of Schneier’s polemic.

Rounding up his attack on cryptocurrencies, Schneier states that blockchain immutability is a problem because in the event of a mistake, “all of your life savings could be gone.” In his view, cryptocurrency is inherently useless and not needed.

19 junho 2019

Auditoria de Criptmoeda - Parte 2

A PwC anunciou a criação de um software para a auditoria de criptmoeda. Mas tem um grande limitação no uso desse software, conforme a própria PwC:

“Nossa capacidade de auditar uma entidade envolvida em atividades de criptomoeda é muito influenciada pelo ambiente de controle de nossos clientes e, nesse estágio, pela amplitude de tokens suportados por nosso software Halo. Essas considerações serão fundamentais para determinar se nos sentimos confortáveis em aceitar um compromisso de auditoria”.

“Nossa capacidade de auditar uma entidade envolvida em atividades de criptomoeda é muito influenciada pelo ambiente de controle de nossos clientes e, nesse estágio, pela amplitude de tokens suportados por nosso software Halo. Essas considerações serão fundamentais para determinar se nos sentimos confortáveis em aceitar um compromisso de auditoria”.

Parece que a PwC está muito mais interessada em surfar na onda das criptmoedas e do bitcoin. A competição, busca por inovação e marketing faz parte dos negócios. Como tem muito gente falando dessa tema, a PwC logo tratou de anunciar uma solução para o tema.

Eu tenho a mesma opinião do professor de criptografia de Harvard Bruce Schneier:

“If your bitcoin exchange gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If your bitcoin wallet gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If you forget your login credentials, you lose all of your money. If there’s a bug in the code of your smart contract, you lose all of your money. If someone successfully hacks the blockchain security, you lose all of your money. In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit?

Ou seja, blockchain e bitcoin são inúteis.

Ou seja, blockchain e bitcoin são inúteis.

Nasa acusada de manipular custos

Pense em uma entidade confiável. Nasa? Não mais. A entidade responsável pelo programa espacial dos Estados Unidos pretendia levar astronauta à Lua novamente em 2024 (ou até 2024). Mas uma reportagem do Washington Post descobriu que a entidade tem problemas graves. Um relatório de prestação de contas do governo dos EUA mostrou que o custo real do programa foi manipulado na sua contabilização. Além de falta de transparência sobre os voos tripulados. Na realidade, o GAO, que fez o documento sobre a NASA, afirma que não é possível saber o custo do programa.

Apesar do atraso no programa, a Nasa continuou pagando "prêmios" para Boeing, principal fornecedora do foguete, relacionada com o desempenho. Ou seja, a Boeing atrasou o programa e sua avaliação não mudou.

Uma estimativa do custo do programa: entre 20 a 30 bilhões de dólares em cinco anos. Mas o custo do foguete, a parte mais importante do programa, não é conhecido, segundo o GAO

Apesar do atraso no programa, a Nasa continuou pagando "prêmios" para Boeing, principal fornecedora do foguete, relacionada com o desempenho. Ou seja, a Boeing atrasou o programa e sua avaliação não mudou.

Uma estimativa do custo do programa: entre 20 a 30 bilhões de dólares em cinco anos. Mas o custo do foguete, a parte mais importante do programa, não é conhecido, segundo o GAO

Auditoria de Criptomoeda

Ontem tivemos uma postagem do Pedro Correia sobre a inutilidade do Blochain. Hoje, a PwC anuncia uma solução para auditoria de transações com criptomoeda. A empresa tem um conjunto de ferramentas de auditoria que chamou de "Halo". Agora, entre as soluções, a ferramenta é capaz de

(1) provide independent, substantive evidence of the “private key and public address pairing” which is one of the pieces needed to establish ownership of cryptocurrency

(2) securely interrogate the blockchain to independently and reliably gather corroborating information about blockchain transactions and balances.

(1) provide independent, substantive evidence of the “private key and public address pairing” which is one of the pieces needed to establish ownership of cryptocurrency

(2) securely interrogate the blockchain to independently and reliably gather corroborating information about blockchain transactions and balances.

Caixa-preta do BNDES

A controversa demissão de Joaquim Levy da presidência do BNDES tem um motivo, segundo o presidente da república: a falta de evidenciação. Relatos indicam que Levy recebeu do presidente a missão de "abrir a caixa-preta" do BNDES. Em termos práticos, a investigação de operações de financiamentos do banco desde 2003 a 2016. Alguns meses antes, o ex-presidente do BNDES tinha afirmado que a entidade era a mais transparente do mundo. Assim, há controvérsias sobre a existência ou não de transparência na instituição.

Talvez a questão passe pela missão do BNDES. Durante os governos Lula e Dilma a entidade tinha objetivo de ajudar no crescimento do país. Eis uma discussão interessante da Época Negócios sobre o assunto:

(...) Sob gestão petista, o governo federal repassou recursos volumosos ao BNDES para que ele pudesse ampliar seus empréstimos - isso era feito por meio da emissão de títulos públicos, o que implica em aumento da dívida.

Entre 2008 e 2014, por exemplo, foram injetados no banco R$ 416,1 bilhões com essa finalidade, além de mais R$ 24,7 bilhões com destinação específica para compra de ações da Petrobras com o objetivo de capitalizar a estatal.

O resultado foi que o BNDES atingiu recordes de desembolsos (crédito concedido), chegando ao recorde de R$ 190 bilhões em 2013. A partir de 2016, esses valores caíram bruscamente, ficando em R$ 69,3 bilhões em 2018.

O crescimento das operações veio acompanhado de alta nos resultados. Em valores atualizados pela inflação, o lucro anual do banco passou de uma média de R$ 2,7 bilhões entre 2001 e 2004 para R$ 11,7 bilhões entre 2005 e 2014. Desde 2015, tem ficado abaixo de R$ 7 bilhões, refletindo o enxugamento.

Muitas das operações realizadas durante esse boom dos governos do PT, porém, viraram alvo de questionamentos.

Algumas delas foram os empréstimos para obras realizadas por empreiteiras brasileiras no exterior, em países como Venezuela, Cuba e Moçambique. As dívidas não têm sido pagas - o débito dos três países por causa dos atrasos já soma mais de R$ 2 bilhões.

(...) Além das obras financiadas no exterior, outra fonte de polêmica sobre o BNDES durante os governos do PT foram os empréstimos para grandes empresas crescerem e se internacionalizarem - conhecida como política dos "campeões nacionais".

Entre elas, a processadora de carne JBS, cujos executivos confessaram em acordos de delação terem praticado corrupção, e a operadora de telefonia Oi, que passou por recuperação judicial.

Para completar, não havia transparência sobre essas operações, já que o BNDES alegava que isso violaria o sigilo bancário das empresas. No entanto, após grande pressão de órgãos de controle e da opinião pública, o banco foi obrigado a abrir seus dados a partir de 2015, ainda no governo Dilma.

Naquele ano, o Supremo Tribunal Federal (STF) determinou que o BNDES atendesse a uma solicitação do Tribunal de Contas da União (TCU) para detalhar operações financeiras de R$ 7,5 bilhões com o grupo JBS. Com a decisão, o banco passou a atender a todos os pedidos do órgão de controle.

Depois, criou em seu site uma área de transparência, em que detalha as operações, e publicou recentemente o Livro Verde, com um balanço de 340 páginas da sua atuação entre 2001 e 2016.

Nesse documento, o BNDES procurou também responder às críticas sobre o financiamento de obras em países alinhados ideologicamente com os governos do PT. O banco afirma que não financia obras, mas "exportações de serviços de engenharia" do Brasil, já que os recursos emprestados para governos estrangeiros só podem ser usados para pagar empresas brasileiras.

continue lendo aqui

Talvez a questão passe pela missão do BNDES. Durante os governos Lula e Dilma a entidade tinha objetivo de ajudar no crescimento do país. Eis uma discussão interessante da Época Negócios sobre o assunto:

(...) Sob gestão petista, o governo federal repassou recursos volumosos ao BNDES para que ele pudesse ampliar seus empréstimos - isso era feito por meio da emissão de títulos públicos, o que implica em aumento da dívida.

Entre 2008 e 2014, por exemplo, foram injetados no banco R$ 416,1 bilhões com essa finalidade, além de mais R$ 24,7 bilhões com destinação específica para compra de ações da Petrobras com o objetivo de capitalizar a estatal.

O resultado foi que o BNDES atingiu recordes de desembolsos (crédito concedido), chegando ao recorde de R$ 190 bilhões em 2013. A partir de 2016, esses valores caíram bruscamente, ficando em R$ 69,3 bilhões em 2018.

O crescimento das operações veio acompanhado de alta nos resultados. Em valores atualizados pela inflação, o lucro anual do banco passou de uma média de R$ 2,7 bilhões entre 2001 e 2004 para R$ 11,7 bilhões entre 2005 e 2014. Desde 2015, tem ficado abaixo de R$ 7 bilhões, refletindo o enxugamento.

Muitas das operações realizadas durante esse boom dos governos do PT, porém, viraram alvo de questionamentos.

Algumas delas foram os empréstimos para obras realizadas por empreiteiras brasileiras no exterior, em países como Venezuela, Cuba e Moçambique. As dívidas não têm sido pagas - o débito dos três países por causa dos atrasos já soma mais de R$ 2 bilhões.

(...) Além das obras financiadas no exterior, outra fonte de polêmica sobre o BNDES durante os governos do PT foram os empréstimos para grandes empresas crescerem e se internacionalizarem - conhecida como política dos "campeões nacionais".

Entre elas, a processadora de carne JBS, cujos executivos confessaram em acordos de delação terem praticado corrupção, e a operadora de telefonia Oi, que passou por recuperação judicial.

Para completar, não havia transparência sobre essas operações, já que o BNDES alegava que isso violaria o sigilo bancário das empresas. No entanto, após grande pressão de órgãos de controle e da opinião pública, o banco foi obrigado a abrir seus dados a partir de 2015, ainda no governo Dilma.

Naquele ano, o Supremo Tribunal Federal (STF) determinou que o BNDES atendesse a uma solicitação do Tribunal de Contas da União (TCU) para detalhar operações financeiras de R$ 7,5 bilhões com o grupo JBS. Com a decisão, o banco passou a atender a todos os pedidos do órgão de controle.

Depois, criou em seu site uma área de transparência, em que detalha as operações, e publicou recentemente o Livro Verde, com um balanço de 340 páginas da sua atuação entre 2001 e 2016.

Nesse documento, o BNDES procurou também responder às críticas sobre o financiamento de obras em países alinhados ideologicamente com os governos do PT. O banco afirma que não financia obras, mas "exportações de serviços de engenharia" do Brasil, já que os recursos emprestados para governos estrangeiros só podem ser usados para pagar empresas brasileiras.

continue lendo aqui

18 junho 2019

Petrobras não foi vítima

Muito antes da Petrobras reconhecer o problema de corrupção, uma investigação interna realizada na empresa já apontava operações suspeitas, informa a Reuters. A empresa descobriu em 2012 que estava pagando muito caro por produtos de petróleo. Um ano depois, alguns funcionários recomendaram a interrupção das transações com uma empresa em particular, a Seaview, que fazia regularmente esta operação. Mas as operações continuaram.

Segundo a investigação realizada agora, quatro grandes empresas de commodities do mundo - Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore e Mercuria - usavam a Seaview e outras empresas para pagar propinas para funcionários da Petrobras. As operações eram rotineiras entre 2011 e 2014 e ocorriam em Cingapura.

Anteriormente, a empresa alegou de forma sistemática que era “vítima” involuntária da corrupção. Muitos acreditaram nesta história (aqui também). Nas demonstrações de 2016 a empresa tentou reescrever a história do escândalo. Mas o fato de existir uma investigação interna que descobriu um problema de corrupção mostra que esta narrativa não convence, afirmou a Reuters.

In the first months of 2013, an internal debate emerged at Petrobras about whether to halt business with Seaview, according to the documents and the people. Petrobras declined to do so, they said, after some senior managers argued that the oil company could lose money by limiting the number of brokers it interacts with.

Segundo a investigação realizada agora, quatro grandes empresas de commodities do mundo - Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore e Mercuria - usavam a Seaview e outras empresas para pagar propinas para funcionários da Petrobras. As operações eram rotineiras entre 2011 e 2014 e ocorriam em Cingapura.

Anteriormente, a empresa alegou de forma sistemática que era “vítima” involuntária da corrupção. Muitos acreditaram nesta história (aqui também). Nas demonstrações de 2016 a empresa tentou reescrever a história do escândalo. Mas o fato de existir uma investigação interna que descobriu um problema de corrupção mostra que esta narrativa não convence, afirmou a Reuters.

In the first months of 2013, an internal debate emerged at Petrobras about whether to halt business with Seaview, according to the documents and the people. Petrobras declined to do so, they said, after some senior managers argued that the oil company could lose money by limiting the number of brokers it interacts with.

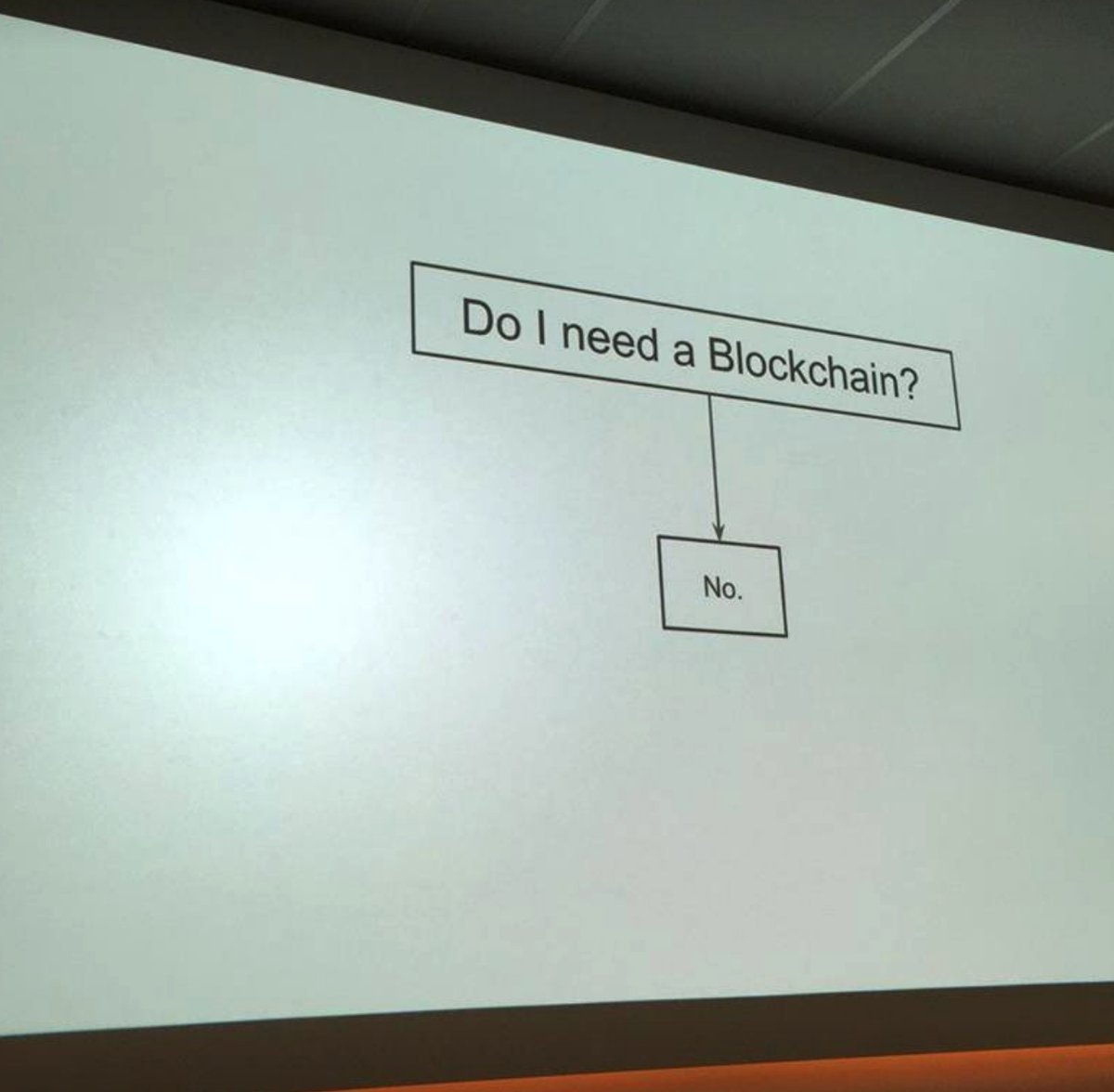

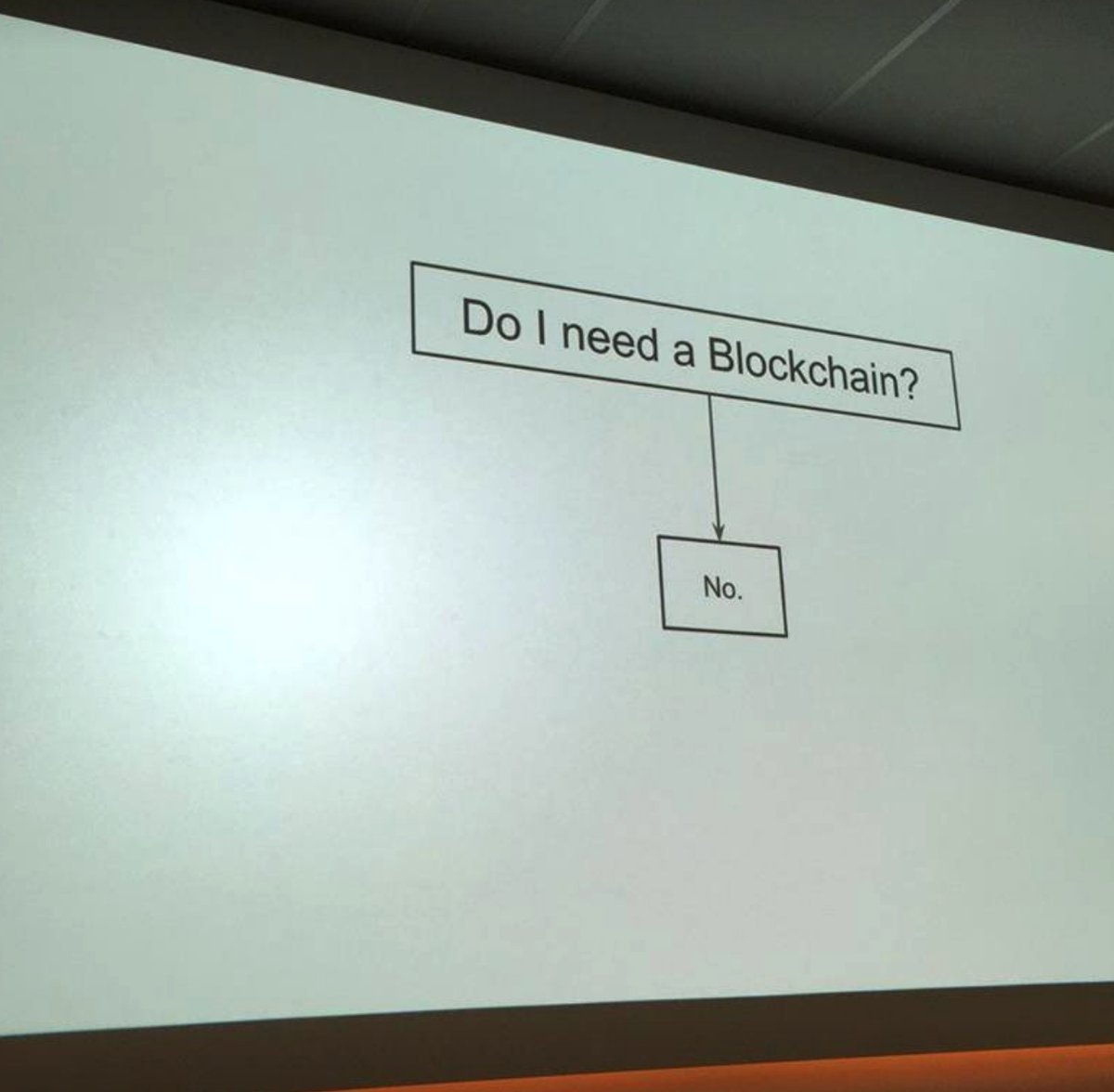

Blockchain é inútil

Ótimo artigo do professor Bruce Schneier, especialista em segurança digital e professor da Universidade de Harvard, sobre o Blockchain:

[...]

Much has been written about blockchains and how they displace, reshape, or eliminate trust. But when you analyze both blockchain and trust, you quickly realize that there is much more hype than value. Blockchain solutions are often much worse than what they replace.

What blockchain does is shift some of the trust in people and institutions to trust in technology. You need to trust the cryptography, the protocols, the software, the computers and the network. And you need to trust them absolutely, because they’re often single points of failure.

When that trust turns out to be misplaced, there is no recourse. If your bitcoin exchange gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If your bitcoin wallet gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If you forget your login credentials, you lose all of your money. If there’s a bug in the code of your smart contract, you lose all of your money. If someone successfully hacks the blockchain security, you lose all of your money. In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit?

Blockchain enthusiasts point to more traditional forms of trust—bank processing fees, for example—as expensive. But blockchain trust is also costly; the cost is just hidden. For bitcoin, that's the cost of the additional bitcoin mined, the transaction fees, and the enormous environmental waste.

Blockchain doesn’t eliminate the need to trust human institutions. There will always be a big gap that can’t be addressed by technology alone. People still need to be in charge, and there is always a need for governance outside the system. This is obvious in the ongoing debate about changing the bitcoin block size, or in fixing the DAO attackagainst Ethereum. There’s always a need to override the rules, and there’s always a need for the ability to make permanent rules changes. As long as hard forks are a possibility—that’s when the people in charge of a blockchain step outside the system to change it—people will need to be in charge.

Any blockchain system will have to coexist with other, more conventional systems. Modern banking, for example, is designed to be reversible. Bitcoin is not. That makes it hard to make the two compatible, and the result is often an insecurity. Steve Wozniak was scammed out of $70K in bitcoin because he forgot this.

These issues are not bugs in current blockchain applications, they’re inherent in how blockchain works. Any evaluation of the security of the system has to take the whole socio-technical system into account. Too many blockchain enthusiasts focus on the technology and ignore the rest.

To the extent that people don’t use bitcoin, it’s because they don’t trust bitcoin. That has nothing to do with the cryptography or the protocols. In fact, a system where you can lose your life savings if you forget your key or download a piece of malware is not particularly trustworthy. No amount of explaining how SHA-256 works to prevent double-spending will fix that.

Similarly, to the extent that people do use blockchains, it is because they trust them. People either own bitcoin or not based on reputation; that’s true even for speculators who own bitcoin simply because they think it will make them rich quickly. People choose a wallet for their cryptocurrency, and an exchange for their transactions, based on reputation. We even evaluate and trust the cryptography that underpins blockchains based on the algorithms’ reputation.

To see how this can fail, look at the various supply-chain security systems that are using blockchain. A blockchain isn’t a necessary feature of any of them. The reasons they’re successful is that everyone has a single software platform to enter their data in. Even though the blockchain systems are built on distributed trust, people don’t necessarily accept that. For example, some companies don’t trust the IBM/Maersk system because it’s not their blockchain.

Irrational? Maybe, but that’s how trust works. It can’t be replaced by algorithms and protocols. It’s much more social than that.

Still, the idea that blockchains can somehow eliminate the need for trust persists. Recently, I received an email from a company that implemented secure messaging using blockchain. It said, in part: “Using the blockchain, as we have done, has eliminated the need for Trust.” This sentiment suggests the writer misunderstands both what blockchain does and how trust works.

Do you need a public blockchain? The answer is almost certainly no. A blockchain probably doesn’t solve the security problems you think it solves. The security problems it solves are probably not the ones you have. (Manipulating audit data is probably not your major security risk.) A false trust in blockchain can itself be a security risk. The inefficiencies, especially in scaling, are probably not worth it. I have looked at many blockchain applications, and all of them could achieve the same security properties without using a blockchain—of course, then they wouldn’t have the cool name.

Honestly, cryptocurrencies are useless. They're only used by speculators looking for quick riches, people who don't like government-backed currencies, and criminals who want a black-market way to exchange money.

To answer the question of whether the blockchain is needed, ask yourself: Does the blockchain change the system of trust in any meaningful way, or just shift it around? Does it just try to replace trust with verification? Does it strengthen existing trust relationships, or try to go against them? How can trust be abused in the new system, and is this better or worse than the potential abuses in the old system? And lastly: What would your system look like if you didn’t use blockchain at all?

If you ask yourself those questions, it's likely you'll choose solutions that don't use public blockchain. And that'll be a good thing—especially when the hype dissipates.

[...]

Much has been written about blockchains and how they displace, reshape, or eliminate trust. But when you analyze both blockchain and trust, you quickly realize that there is much more hype than value. Blockchain solutions are often much worse than what they replace.

[...]

When that trust turns out to be misplaced, there is no recourse. If your bitcoin exchange gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If your bitcoin wallet gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If you forget your login credentials, you lose all of your money. If there’s a bug in the code of your smart contract, you lose all of your money. If someone successfully hacks the blockchain security, you lose all of your money. In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit?

Blockchain enthusiasts point to more traditional forms of trust—bank processing fees, for example—as expensive. But blockchain trust is also costly; the cost is just hidden. For bitcoin, that's the cost of the additional bitcoin mined, the transaction fees, and the enormous environmental waste.

Blockchain doesn’t eliminate the need to trust human institutions. There will always be a big gap that can’t be addressed by technology alone. People still need to be in charge, and there is always a need for governance outside the system. This is obvious in the ongoing debate about changing the bitcoin block size, or in fixing the DAO attackagainst Ethereum. There’s always a need to override the rules, and there’s always a need for the ability to make permanent rules changes. As long as hard forks are a possibility—that’s when the people in charge of a blockchain step outside the system to change it—people will need to be in charge.

Any blockchain system will have to coexist with other, more conventional systems. Modern banking, for example, is designed to be reversible. Bitcoin is not. That makes it hard to make the two compatible, and the result is often an insecurity. Steve Wozniak was scammed out of $70K in bitcoin because he forgot this.

[..]

These issues are not bugs in current blockchain applications, they’re inherent in how blockchain works. Any evaluation of the security of the system has to take the whole socio-technical system into account. Too many blockchain enthusiasts focus on the technology and ignore the rest.

To the extent that people don’t use bitcoin, it’s because they don’t trust bitcoin. That has nothing to do with the cryptography or the protocols. In fact, a system where you can lose your life savings if you forget your key or download a piece of malware is not particularly trustworthy. No amount of explaining how SHA-256 works to prevent double-spending will fix that.

Similarly, to the extent that people do use blockchains, it is because they trust them. People either own bitcoin or not based on reputation; that’s true even for speculators who own bitcoin simply because they think it will make them rich quickly. People choose a wallet for their cryptocurrency, and an exchange for their transactions, based on reputation. We even evaluate and trust the cryptography that underpins blockchains based on the algorithms’ reputation.

To see how this can fail, look at the various supply-chain security systems that are using blockchain. A blockchain isn’t a necessary feature of any of them. The reasons they’re successful is that everyone has a single software platform to enter their data in. Even though the blockchain systems are built on distributed trust, people don’t necessarily accept that. For example, some companies don’t trust the IBM/Maersk system because it’s not their blockchain.

Irrational? Maybe, but that’s how trust works. It can’t be replaced by algorithms and protocols. It’s much more social than that.

Still, the idea that blockchains can somehow eliminate the need for trust persists. Recently, I received an email from a company that implemented secure messaging using blockchain. It said, in part: “Using the blockchain, as we have done, has eliminated the need for Trust.” This sentiment suggests the writer misunderstands both what blockchain does and how trust works.

Do you need a public blockchain? The answer is almost certainly no. A blockchain probably doesn’t solve the security problems you think it solves. The security problems it solves are probably not the ones you have. (Manipulating audit data is probably not your major security risk.) A false trust in blockchain can itself be a security risk. The inefficiencies, especially in scaling, are probably not worth it. I have looked at many blockchain applications, and all of them could achieve the same security properties without using a blockchain—of course, then they wouldn’t have the cool name.

Honestly, cryptocurrencies are useless. They're only used by speculators looking for quick riches, people who don't like government-backed currencies, and criminals who want a black-market way to exchange money.

To answer the question of whether the blockchain is needed, ask yourself: Does the blockchain change the system of trust in any meaningful way, or just shift it around? Does it just try to replace trust with verification? Does it strengthen existing trust relationships, or try to go against them? How can trust be abused in the new system, and is this better or worse than the potential abuses in the old system? And lastly: What would your system look like if you didn’t use blockchain at all?

If you ask yourself those questions, it's likely you'll choose solutions that don't use public blockchain. And that'll be a good thing—especially when the hype dissipates.

Fonte: aqui

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)